AS: You’ve been busy this year with a solo show at Wilkinson and the British Art Show 7. Do deadlines affect how you work?

PU: I find that it’s important to put deadlines out of my mind. I mean they’re there, but I don’t make work specifically for a show because I make what I make. But, as it gets nearer, you can’t help looking at what you have and what would go where and those kinds of decisions.

AS: I imagine the way you work can be unpredictable. You don’t use images. It’s all coming from your own experiences, from what’s in your mind, looking at things and seeing opportunities for paintings.

PU: That’s true, and because I don’t know what any of the paintings will look like when they’re finished, that’s part of it. I like that working process of being surprised by how something might look but that also means that it’s important to be comfortable with failure in the work in terms of making something, looking at it and then thinking it’s not quite right. It might be an interesting idea but the size is wrong or something, I really respond to how it looks in the studio.

AS: What do you do if you see something failing, do you try to make it work or do you scrap it and try something else?

PU: Sometimes I try to make it work. Sometimes I try for months, and then it’s scrapped. Or I try for months and it works. I might think at the time that it was a bad idea in the first place, so it’s never going to work. But then I find I might be drawn to the idea again and have another go at it a year later. There’s enough tension to get an image to work so if you’re getting too self-conscious and wound up, then that’s not helpful.

AS: The painting ends up looking too fraught or contrived?

PU: I think there’s an element of tension in all of them. They’re not completely relaxed paintings but if there’s too much tension then I think a painting can look nervous. And then it’s not doing the job of communicating something. I mean it might be interesting to make a painting about being nervous but then it has to communicate that well, rather than be apologetic of itself. That’s when they get scrapped; if I feel they’re like that.

AS: I’m looking at the girl figure in your earlier work, is it you or is that too obvious?

AS: I’m looking at the girl figure in your earlier work, is it you or is that too obvious?

PU: It’s not meant to be, none of the people I paint are portraits. I think of them as being portraits for feelings rather than portraits of a particular person. But all of my paintings and subjects end up being things that I’ve experienced in some way. They’re not personal stories, but in order for me to explain what something might have felt like or a relationship to an object, in terms of space or colour or scale, then I need to have experienced it. There’s nothing fantastical about them.

AS: Are you losing the figure more, moving in an abstract direction?

PU: I can’t imagine ever being completely abstract because the aspect I’m most interested in is the relationship between a visual world that everyone experiences and how that is explored through materials and marks.

AS: You need something recognisable?

PU: In order to communicate this subject, yes. So the subject is actually really important. For me, it’s not a pure interest in paint and colour and painting. It’s also about these relationships. For me it’s a springboard into different atmospheres or moods or tensions.

AS: And they are invisible things.

PU: Yes, Self Consciousness is very much about painting a feeling. Or the subject of Brick Wall was the everyday but also the formal qualities of painting because it’s a flat painting about something flat. So I’m interested in these subjects that explore a visual everyday world but also the world of the painting and the object itself.

PU: This is one book. It’s falling apart. When I work here I put in lots of different coloured papers and respond to marks and colours and so on in an intuitive way. I’m not working in the book from beginning to end. It’s developed as a whole. I have to feel excited or engaged with the page and if I don’t then I just move on. I’ve worked on these for a while and the only rule I have is that anything can go in them. It can be an insignificant thing like a note of a couple of colours that I like or it can be something about an actual place or an image that has been layered and built up. I describe this as somewhere to be really gentle with ideas so they don’t have to stand up for themselves yet. They might never be used for a painting. I like working with this size. I’ve tried working in smaller or larger books but this size is just right. I also like that they’re quite thick because they start to build up a rich body of images. This is where I begin with all the different types of materials. I use acrylic, graphite, pastel, ink, and printed papers. And using coloured papers gets away from that feeling of a white, empty, blank page.

AS: When it comes to a painting, is there a white blank canvas or do you have to mess it up first?

PU: I think I need to mess it up but I’m not intentionally messing it up. I’ll think I’m just starting a painting but at every stage I’m looking at that and responding to the scale and the way the colours are because they’re not planned. Whatever I feel the subject demands will change my approach. Brick Wall started in a relatively controlled way by making a background of bricks, almost like creating a space to work within and respond to. So I knew I was making a painting of a brick wall and I knew how I was going to begin, but I didn’t know what it would end up looking like or how it would feel working within that pattern or that scale or combination of colours. Something like Self-Consciousness was started by putting colours and textures together, especially the oil paint which was quite impasto, and seeing and feeling where the painting would go. So building up to the image, rather than beginning with an image and working within that. They each have different approaches.

PU: I think I need to mess it up but I’m not intentionally messing it up. I’ll think I’m just starting a painting but at every stage I’m looking at that and responding to the scale and the way the colours are because they’re not planned. Whatever I feel the subject demands will change my approach. Brick Wall started in a relatively controlled way by making a background of bricks, almost like creating a space to work within and respond to. So I knew I was making a painting of a brick wall and I knew how I was going to begin, but I didn’t know what it would end up looking like or how it would feel working within that pattern or that scale or combination of colours. Something like Self-Consciousness was started by putting colours and textures together, especially the oil paint which was quite impasto, and seeing and feeling where the painting would go. So building up to the image, rather than beginning with an image and working within that. They each have different approaches.

AS: You’ve used patterned papers in your sketchbooks, like the chequerboard. What does pattern do for you in a painting?

PU: I used a lot of pattern in the last show. The printed chequerboard and brickwork papers in the sketchbook, is where I first thought of it for painting. The pattern I have been using recently is about exploring a certain sort of rhythm in the paintings. I describe it as a constant hum or drumbeat. It’s a space to work within, which then gets interrupted or, like in Three Bananas, it’s reversed because the background is stronger than the subject on it. The banana shapes are like stains, almost like something has been taken away. So the movement and the focus of the painting is the chequerboard which is also a hand made mark, it’s not really a neat chequerboard so that was important. And then with Brick Wall there are elements where I’ve masked off the pattern which is much more graphic and controlled but then that pattern is echoed and mimicked in handmade brick marks using the different reds. So sometimes its about interrupting something and also an echo or reverberation of a mark or colour.

PU: I used a lot of pattern in the last show. The printed chequerboard and brickwork papers in the sketchbook, is where I first thought of it for painting. The pattern I have been using recently is about exploring a certain sort of rhythm in the paintings. I describe it as a constant hum or drumbeat. It’s a space to work within, which then gets interrupted or, like in Three Bananas, it’s reversed because the background is stronger than the subject on it. The banana shapes are like stains, almost like something has been taken away. So the movement and the focus of the painting is the chequerboard which is also a hand made mark, it’s not really a neat chequerboard so that was important. And then with Brick Wall there are elements where I’ve masked off the pattern which is much more graphic and controlled but then that pattern is echoed and mimicked in handmade brick marks using the different reds. So sometimes its about interrupting something and also an echo or reverberation of a mark or colour.

AS: Do the same motifs crop up?

AS: Do the same motifs crop up?

PU: They do but in the sketchbook they’re not judged too much, they just live there. Elements of them are used when I’m ready to use them but very rarely are they scaled up from here. There might be an element of a composition that I take from the book but usually it’s a material element.

AS: There doesn’t seem to be any hierarchy with the different materials.

AS: I’m surprised you said that was a table, it’s looking down from above.

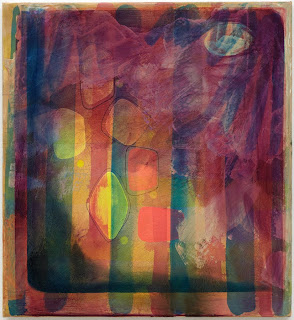

PU: That’s like Sponge Palette in a way, it’s a palette with the thumbhole, and so you’re looking at it from above. Again, there’s pattern, and the sort of echoing of that background pattern and also a combination of colours about painting itself. I called it Sponge Palette because one aspect is that colour and form, for me, are indistinguishable from the subject when they are worked up. That’s my aim in a painting, to achieve, if I feel that I can, the colours and forms to be just those ones necessary for the painting, not to have any that don’t need to be there. So in a sense, the subject of the painting is as inspired by the colour and form. I almost see a subject in a colour combination in a painting in the way that it almost feels like a sponge or something, that the painting becomes saturated with these feelings or atmospheres.

PU: That’s like Sponge Palette in a way, it’s a palette with the thumbhole, and so you’re looking at it from above. Again, there’s pattern, and the sort of echoing of that background pattern and also a combination of colours about painting itself. I called it Sponge Palette because one aspect is that colour and form, for me, are indistinguishable from the subject when they are worked up. That’s my aim in a painting, to achieve, if I feel that I can, the colours and forms to be just those ones necessary for the painting, not to have any that don’t need to be there. So in a sense, the subject of the painting is as inspired by the colour and form. I almost see a subject in a colour combination in a painting in the way that it almost feels like a sponge or something, that the painting becomes saturated with these feelings or atmospheres.

AS: It’s an interesting way to describe a painting, like a sponge, like it sucks in all this stuff, ideas and materials, and becomes visible.

PU: I’m making it sound quite mystical. There are definitely a lot of felt qualities that are really important to me. And it is that thing about a sponge of sucking things up, the subject becoming really imbedded and saturated in the painting itself and in the colours and shapes, but there’s another element. The rigorous editing and appraisal of the work is really important to me. There are real formal aspects that come into play, especially as the painting gets further on, where I’ll be really thinking is it working in terms of subject, is it working in terms of scale and in terms of the painting itself.

AS: It sounds like you’re very controlled about what goes in.

PU: I am but when you speak about paintings in retrospect, because you’re talking about all the ideas, you can’t help but make it sound like ‘when I got to this point I was thinking this …’. But, when I’m actually working on a painting, I wouldn’t necessarily be able to put into words why I chose to get rid of a whole section or decided a painting failed, because I’m working really close to it, and working very quickly, but also so close to instinct and response.

AS: Can you describe the process for making Sponge Palette?

PU: The ground of Sponge Palette is made with an acrylic medium called crackle paste so it’s breaking up the surface. It’s meant to and it makes the surface very spongy. It feels absorbent. Because of the little cracks, the paints run into each other. Different surfaces in paintings are as important as marks because it completely changes the marks on top. I find that quite fascinating. Again, the pattern was made first so I’m working on something that is already visually dense. This palette shape, almost like a picture frame, is translucent so that the pattern is visible almost all the way through it. There would have been, in this painting especially, a real interest in layering and communicating the kind of time and visual conversation that happened in the painting. Some of my other paintings are more sparse and economical in line so they don’t have that sense of layered time. They would be about some other atmospheres or moods or tensions that I’m interested in exploring.

Sponge Palette, 2010 can be seen at Fade Away, Gallery North, Newcastle, 5-24 May 2011

Images courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery

Images:

Sponge Palette, 2010

Girl, 2009

studio photograph, 2011

Self Consciousness, 2010

Three Bananas, 2010

Brick Wall, 2011

studio photograph, 2011

Sponge Palette, 2010